Yiddish

Yiddish is a Jewish-European language containing various dialects that vary according to different Jewish immigrant groups around the world. Our Rebbes spoke and often taught their Torah in Yiddish, and a large portion of the Rebbe's teachings were originally published in this language.

Origins of the Language[edit | edit source]

The language emerged following the migration of many Jews from Ashkenaz (Germany) nearly a thousand years ago, primarily to Eastern European countries, especially Poland. They brought medieval German to Eastern Europe, where it mixed with local Slavic languages. The expulsion of most French Jews in 5154 (except for Provence Jews who were expelled about two hundred years later) and their partial migration to Eastern Europe also influenced Yiddish's development.

Modern Yiddish consists mainly of medieval German (in a slightly different dialect), with many words from various Slavic languages - primarily Russian, Polish, and Ukrainian, as well as Old French. The Holy Tongue (Hebrew) had a central influence on Yiddish, with hundreds of its words incorporated into Yiddish. Almost all Yiddish words referring to holy items and holidays are actually from Hebrew. Many Aramaic words were also added to Yiddish.

Different dialects developed in Yiddish, divided by regions in Eastern Europe. Today, special dialects have also developed in Israel, particularly in Jerusalem. In the United States, Jews' Yiddish has been heavily influenced by English, and many Yiddish speakers speak Yinglish (Yiddish mixed with English). Yiddish has also had some influence on English slang in the United States, particularly in New York where many Jews live.

Writing in Yiddish[edit | edit source]

In 1925, a group of Yiddishists in Vilna, Lithuania, decided to establish uniform writing rules in Yiddish called "YIVO rules." The Orthodox Jewish community did not accept these rules at the time, but today most write almost according to these rules.

The Orthodox distanced themselves from these rules because the institution was suspected of heresy and closeness to Zionism. The Soviets objected because they opposed Hebrew words in their Hebrew spelling and wrote, for example, "shabes" instead of "Shabbat" and "khazen" instead of "chazan." The Chassidim would joke about this writing style, saying "By them 'truth' - Emes is without an aleph, and 'troubles' - Tzoros- without an end..."[1]

However, it was established in Yiddish - and this is accepted by both the Orthodox and YIVO rule founders - that words originating from Hebrew are written as they appear in their original form.

Yiddish by Chassidism[edit | edit source]

In the Chassidic world, Yiddish holds a special place:

The Baal Shem Tov, The Maggid of Mezritch, the Alter Rebbe, and all our Rebbes taught Torah specifically in Yiddish, not in Hebrew. This was done to better communicate the teachings and make them more accessible to the common person's understanding.

The use of Yiddish in teaching Chassidic concepts had significant importance, as it allowed for better comprehension and internalization of the teachings than when heard in Hebrew, which people were less familiar with in daily life.

Modern Usage[edit | edit source]

There are several testimonies from the Rebbe's family encouraging the use of Yiddish. For example, when the Rebbe's emissary in Washington, Rabbi Levi Shemtov, went to receive a blessing from Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka before his wedding, she verified if he was the grandson of Rabbi Bentzion Shemtov, and upon confirmation said, "If so, very good, because now I'm sure your children will speak Yiddish..."

The Rebbe showed particular interest in maintaining Yiddish as a living language within the Chabad community, sometimes expressing concern when young Chassidim would speak English instead of Yiddish among themselves.

Regarding the use and teaching of Yiddish in education, the Rebbe wrote that while the main purpose of education is to instill fear and love of God and Torah study, the language of instruction should be determined by what best serves these goals and should be decided by the majority of parents.

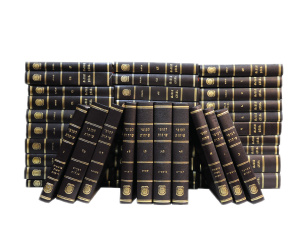

Yiddish Works and Publications[edit | edit source]

The Mitteler Rebbe:

- Kuntres Pokeach Ivrim

The Tzemach Tzedek:

- Shema Yisrael (which he said to the Cantonists)

- Mizmor Shir L'Yom HaShabbat

- Achas Shoalti

The Previous Rebbe published many articles in Yiddish in the "HaKriah V'HaKedushah" periodicals, as well as numerous articles in the "Chicago Visit" booklet.

Educational Approach to Yiddish[edit | edit source]

When Rabbi Ben Tzion Vishetzky opened Oholei Torah in Kfar Chabad and brought his child to a private audience with the Rebbe, the Rebbe tested the child in Yiddish about what he had learned in cheder. The child answered in Hebrew because he wasn't fluent enough in Yiddish. The questions had to be translated for the child occasionally. When the Rebbe asked the child "What color is your jacket?" in Yiddish, it became clear that the Rebbe was testing the child's Yiddish knowledge. When the child couldn't answer, his father whispered the translation, and the child answered "brown" in Hebrew. The Rebbe then looked at the father and seriously asked, "How does he know Hebrew so well?" adding with surprise, "Don't they teach in Yiddish in cheder?"

On Shabbat Parshat Vayeshev 5748 (1988), the Rebbe questioned how it was possible that young married men, "Top Chabad Chassidim" were speaking English among themselves instead of Yiddish.

Regarding Yiddish instruction in schools, the Rebbe wrote that since the main goal of the institution is education for fear and love of God and Torah study and observance of mitzvot, the primary consideration isn't which language is used (except where language affects matters of religious observance, in which case language becomes important accordingly). The decision should be made according to the majority of parents' wishes. The Rebbe questioned whether acquiring the special qualities of the Yiddish language was the responsibility of the school or of parents and the home environment.

Several educators and emissaries heard from the Rebbe that "children should learn in the language they understand best, through which they will understand more and learn more."

Legacy and Importance[edit | edit source]

The use of Yiddish remains significant in Chassidic communities, particularly in educational and religious contexts. Its preservation helps maintain a connection to the rich heritage of Chassidic teachings while serving as a practical medium for transmitting Torah concepts.

The language continues to evolve and adapt to modern needs while maintaining its traditional role in Jewish life and learning. Its unique ability to express Jewish concepts and its historical significance in Chassidic teaching make it an important part of Jewish cultural and religious heritage.

The Rebbe's approach to Yiddish reflected a balance between preserving tradition and meeting practical educational needs. While emphasizing the language's importance, he also recognized the need to ensure effective communication and learning, particularly for younger generations.

Through various documented instances and teachings, we see how Yiddish served not just as a language but as a vehicle for preserving and transmitting Jewish values and Chassidic teachings across generations, while adapting to the changing needs of different communities and circumstances.

See Also[edit | edit source]

Further Reading[edit | edit source]

- Special compilation of the Rebbe's words on the subject

- Likkutei Sichos Vol. 21 page 447 and onwards, a special talk about the Yiddish language in connection with the Tanya lesson on radio that was delivered in Yiddish.

- Talk from Shabbat Parshat Vayeshev 5748 - Sefer HaSichos 5748 page 158.

- Importance of the Yiddish language, a collection of the Rebbe's words, on the Chabad Youth website in Israel

- "This year too I will speak in Mame Lashon": The Rebbe in private audiences with 'wealthy donors' at 770

External Links[edit | edit source]

- Teach in Yiddish specifically, or not specifically?

- 13 facts about Yiddish that every Jew needs to know • Where does the name Yiddish come from? • Yiddish in the Soviet Union • Why do Jews still insist on speaking Yiddish? (English)

- On learning in Hebrew and in Sephardic pronunciation, in the 'Nitzutzei Rebbe' section, Hiskaserut weekly, Parshat Ki Tisa 5782, page 12

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ without the letter ״ת״