Matzah

Matzah is bread bread made from dough that has not risen. It is a Torah commandment to eat it on the first night of Passover, the Seder night.

Method of Baking[edit | edit source]

The Torah does not provide details about preparing matzah, but according to most halachic authorities, matzah should be made by hand rather than machine, and in a round shape rather than square. The preparation and baking of matzah is done in a special bakery, with extreme care to ensure the dough does not become chametz (leavened) and cause one to transgress by eating chametz.

Matzah is also called "lechem oni"[1] (bread of poverty/affliction), from which the Sages learned that its ingredients should be "poor" - just flour and water. Only with this matzah can one fulfill the mitzvah. Matzah with added liquids besides water is called "matzah ashirah" (enriched matzah), which cannot be used to fulfill the obligation. However, if it is properly made and protected from becoming chametz, it is permitted to be eaten during the holiday. Nevertheless, the custom is not to eat matzah ashirah at all.

Types of Matzah[edit | edit source]

Matzah Shemurah[edit | edit source]

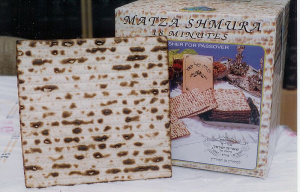

Matzah shemurah (guarded matzah) refers to mehudar (enhanced) matzot baked from flour that has been specially guarded from contact with water from the time of harvesting.

Although there are different levels of "matzah shemurah," today it is customary to call "matzah shemurah" only matzot that have been guarded from contact with water from the time the wheat was harvested.

Machine Matzah[edit | edit source]

Machine matzah refers to matzah whose production stages were done by machine. In many Jewish communities, these matzot are forbidden due to various concerns (such as the potential leavening that occurs to the dough immediately after contact with the machine, and more). This is also the ruling of our Rebbes.

Gebrochts[edit | edit source]

Matzah that comes in contact with water is called "matzah shruyah" (soaked matzah), and people are careful not to eat it out of concern that flour remaining on the matzah that was not baked during the baking process could become chametz when it comes in contact with water.

In Chabad Chassidut, they are extremely careful not to eat gebrochts, except on the last day of Passover when they specifically make a point to eat gebrochts.

In Chassidic Teachings[edit | edit source]

Food of Faith and Healing[edit | edit source]

In the Zohar[2], matzah is called "meichlah d'meheimanuta" - the food of faith, because eating matzah is a segulah (spiritually beneficial action) for increasing faith. In Chassidut, this is explained based on the saying of our Sages: "A baby does not know how to call 'Abba' until it tastes grain.[3]" Similarly, matzah works on the one who eats it so that they will know to call upon Hashem's name and know and recognize His existence.

Another name for matzah in the Zohar is "meichlah d'asvata" - the food of healing. Matzah has a special segulah for healing the sick. A chassid of the Alter Rebbe who was a doctor would receive matzot from the Rebbe during Passover, grind them, and prepare medicines from them.

The Alter Rebbe said that the aspect of "food of faith" is primarily on the first night (outside of Israel, two Seder nights are observed) and the aspect of "food of healing" is primarily on the second night. Because if faith is only awakened after healing from illness, one needs to be ill, but if there is faith from the outset, there is no need for illness and there is constant healing.

Matzah as the Opposite of Pride[edit | edit source]

Chassidic teachings extensively explain the difference between chametz, which represents ego and pride and is a symbol of evil and the evil inclination, and matzah, which represents self-nullification and humility.

This difference is evident in several ways:

- In their form: Chametz is puffed up, coarse and elevated, while matzah is low and humble.

- In their taste: Chametz has a pronounced taste, while matzah doesn't have much taste.

- In their names: "Chametz" and "matzah" contain almost the same letters, and the difference between them is in the letter ה (hei) which becomes ח (chet). The letter chet, which is closed on all sides and open at the bottom, alludes to the sefirah of Malchut as it gives place to the drawing of external forces; while the letter hei, which has an opening from above, alludes to the sefirah of Malchut as it is illuminated by the sefirah of Chochmah, so that external forces cannot receive from it.

See Also[edit | edit source]

External Links[edit | edit source]

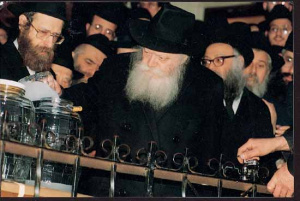

- The Rebbe sends matzot to the Holy Land

- The meticulous process of baking matzot - from "Hidur Mitzvah," part one • part two - grinding the wheat • part three - baking the matzot • part four - finishing the baking